The OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct (OECD Guidelines) require all governments that follow (“adhere to”) the Guidelines to establish a National Contact Point (NCP) – a government-supported office whose core duty is to advance the effectiveness of the OECD Guidelines. NCPs do this in two ways: by promoting and raising awareness about the Guidelines’ standards and the NCP grievance mechanism among businesses, civil society, and other stakeholders; and by handling complaints against companies who allegedly have failed to meet the Guidelines’ standards.

NCPs are also expected or encouraged to engage in other activities, such as promoting national laws and policies on responsible business conduct that align with the Guidelines, participating in the work of the OECD Investment Committee, and learning from peers.

Requirements for NCPs

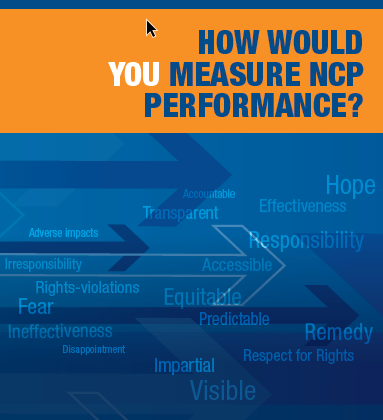

The OECD Guidelines allow governments flexibility to structure their NCP in any way that fits their domestic situation. However, all NCPs must be “functionally equivalent” in their ability to accomplish their dual mandate. The OECD Guidelines require that NCPs operate in accordance with seven core effectiveness criteria. NCPs must operate in a manner that is: visible, accessible, transparent, accountable, impartial and equitable, predictable, and compatible with the Guidelines. Much of OECD Watch’s advocacy focuses on urging NCPs to uphold these requirements.

NCPs’ duties as a grievance mechanism

Each NCP is required to handle complaints of alleged corporate non-observance of the Guidelines. OECD Watch has developed guidance on the NCP complaint process, including the stages of the process.